Mannerism

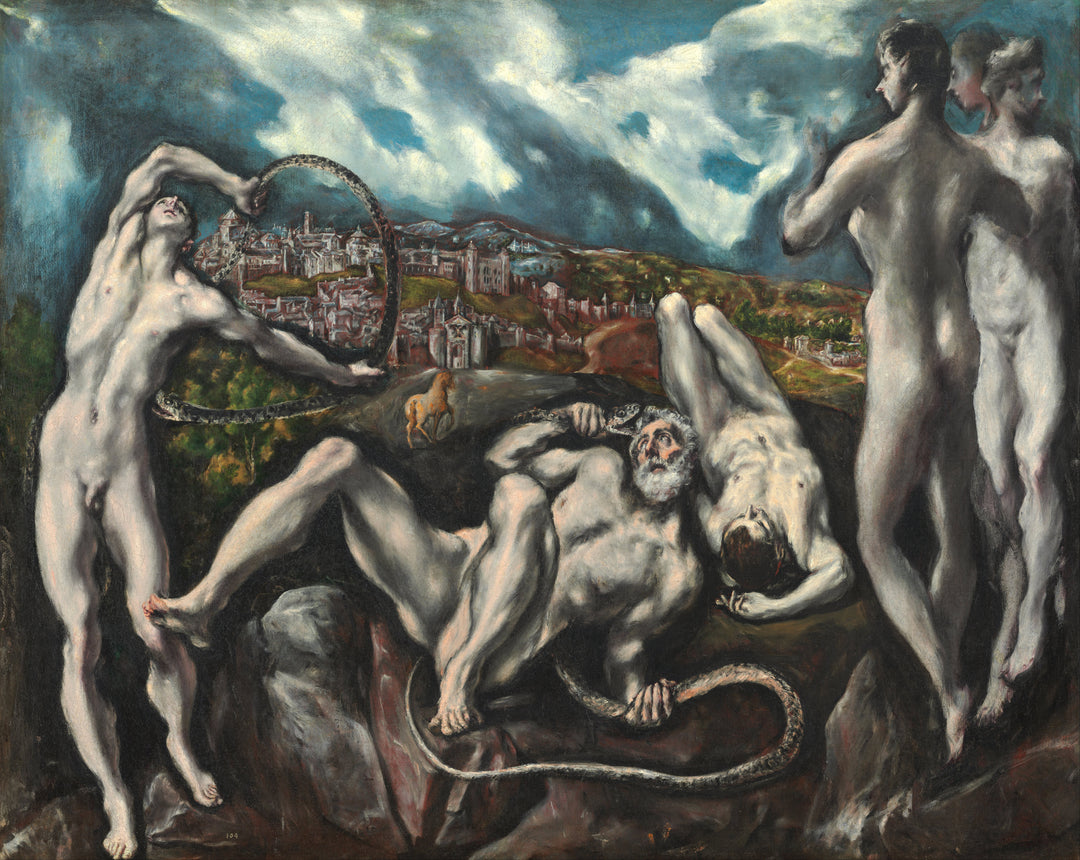

Mannerism emerged in Italy around 1520 as an aesthetic reaction against the compositional balance of the High Renaissance, a movement that had reached its culmination with the works of Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci. Unlike these masters, Mannerist artists began to value compositional tension, spatial ambiguity, and anatomical distortion as expressive devices. The classical ideal of harmony was replaced by a technical virtuosity that challenged established conventions, giving rise to unstable compositions, elongated figures, and intensely contrasted colors. The elongation of the human body no longer adhered to natural canons, but rather to a deliberate pursuit of visual drama and heightened spirituality. For the observer of works belonging to this artistic current, the exaggeration of “the manners”—particularly in the positions of the hands and legs of the figures—is strikingly evident.

Among the leading representatives of this current are Jacopo da Pontormo, whose "Deposition from the Cross" conveys a disconcerting emotional intensity; Rosso Fiorentino, a pioneer of Florentine Mannerism, who infused his compositions with an almost chaotic dynamism; and Parmigianino, whose "Madonna with the Long Neck" encapsulates the essence of Mannerism in its unnatural elegance and complex visual hierarchy. One of the most influential artists associated with Mannerism was Doménikos Theotokópoulos, known as El Greco, who developed his singular style in Spain, fusing Byzantine spirituality with Mannerist distortion. Works such as "The Burial of the Count of Orgaz" and "View of Toledo" demonstrate his expressive use of color, light, and elongated form, projecting a mystical intensity that surpassed Renaissance Naturalism.

Far from being a mere interlude between the Renaissance and the Baroque, Mannerism represents a crucial stage of transition and exploration. Its influence was felt at the dawn of the Baroque, particularly in the taste for theatricality and emotional exaltation, and left its mark on the art of Northern Europe as well as later movements such as Rococo. Even Expressionism in the twentieth century would find in Mannerism precedents for its subjective treatment of the human figure and its formal freedom. Mannerism does not confine itself to the faithful imitation of reality; it exaggerates, distorts, and reinvents it in order to express inner tensions, cultural crises, or profound spiritual concerns.